Jews lived in thriving Kurdish communities for thousands of years.

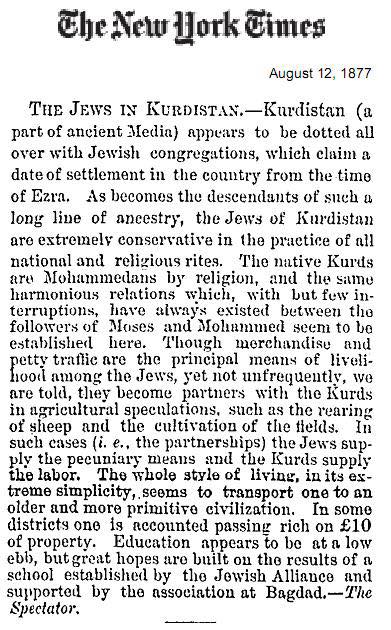

KURDISH JEWS

KURDÊN CIHÛ

Home †|††DestpÍk††|††Ana Sayfa

Jews lived in thriving Kurdish communities for thousands of years.

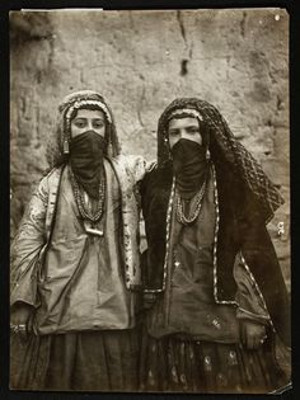

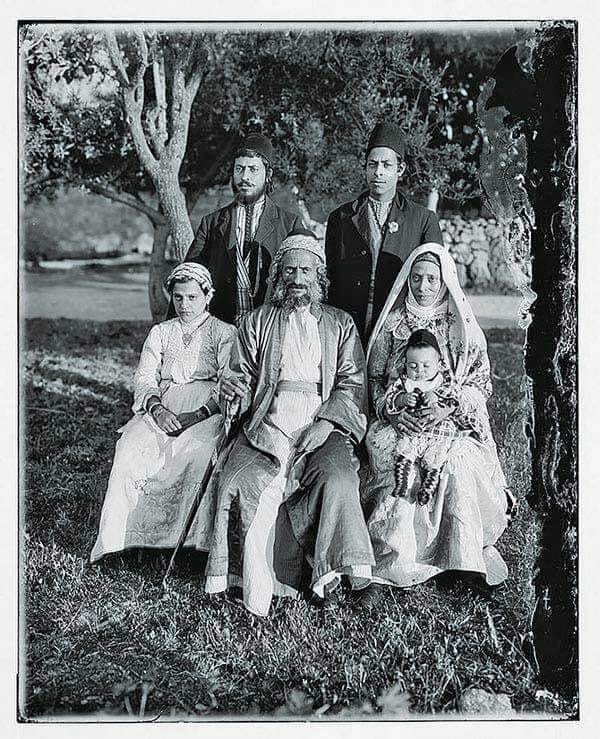

Xanimeka oldar ji Kurdên Cihû, 1910. (by Albert Kahn)

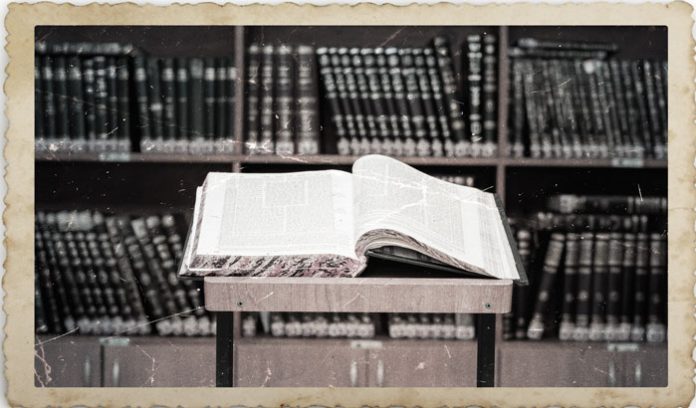

Jews of Kurdistan by Mordechai Zaken

Jews of Kurdistan: 10 Facts

Oct 27, 2019 | by Dr. Yvette Alt Miller

Jews lived in thriving Kurdish communities for thousands of years.

Kurds are one of the oldest and largest ethnic groups in the Middle East. (...)

For much of Kurdish history, Jews were an integral part of life. Persecuted in much of the Middle East, Jewish towns and villages flourished in Kurdish lands. Here are ten little known facts about Jews from Kurdish lands in the past and today.

Ancient Origins

Many Jewish communities in Kurdish lands claim they have lived there for over 2,500 years, ever since the Jews of the northern kingdom of Israel were sent into exile there. The Tanach records that in the 8th Century BCE, “Shalmaneser king of Assyria went up against” the Jewish King Hoshea, invading Jewish lands and laying siege to cities and towns. Eventually, “the king of Assyria captured Samaria and exiled Israel to Assyria. He settled them in Halah, in Habor, by the Gozan River, and in the cities of Media” (Kings II, 17:1-6). These sites listed are within the Kurdish regions of Iran and Central Asia.

For generations, the Jews in Kurdish areas lived in relative isolation. Many worked as farmers and their insular communities developed distinct customs, including marrying at a very young age and praying at the graves of Jewish prophets. The medieval Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited Kurdish areas in 1170 CE and encountered over a hundred Jewish communities in Kurdish lands. One of the largest was Amadiya in current-day "Iraq", where he recorded that the Jewish community numbered about 25,000. Though the largest community of non-Jewish Kurds is found in present-day Turkey, Kurdish Jews lived primarily further east, in modern "Iraq".

Language of the Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud is written in Aramaic, a language that uses Hebrew letters and is closely related to Hebrew, but with some key differences. For generations, Jews living in Kurdish lands maintained Aramaic as their everyday spoken language. They adopted some words from Turkish, Persian, Kurdish, Arabic and Hebrew, but in general spoke an Aramaic very similar to their ancestors in Talmudic times.

Kurdish Jews called their language “Lishna Yahudiya”, meaning the “Jewish Language” or “Lashon Ha’Targum”, meaning “Language of the Translation”, presumably referring to translations of the Torah, or “Lashon HaGalut”, meaning “Language of Exile” (from the land of Israel). Local Arabs called the Jews’ language Jabali, meaning “from the mountains”, referring to where some Jews in Kurdish lands lived.

A Jewish Queen

In the First Century CE, the kingdom of Adiabene in Iran became a loyal part of the Jewish community after the local monarch’s wife, Queen Helene, converted to Judaism and encouraged her subjects to do the same. Kurdish Jews still recall the kingdom of Adiabene in what is today Kurdish lands as part of their unique heritage.

Queen Helene’s remarkable journey is recorded in the writings by the Roman Jewish historian Josephus and in the Talmud (Gittin 60a). Queen Helene and her husband King Monobaz of Adiabene regularly encountered Jewish merchants passing through their lands. Queen Helene was so impressed with Jewish life that she hired a teacher to tutor her in Judaism.

After King Monobaz died, his son Izates took his place on the throne. Like his mother Queen Helene, Izates was also interested in Judaism and the pair learned all they could, first from a Jewish trader named Chananyah, then from a rabbi named Rabbi Eleazar of Galilee. Eventually, the royal family converted to Judaism and encouraged their subjects to do the same. They sent many gifts to the land of Israel, including beautiful golden candelabras and goblets for the Temple in Jerusalem, and shipments of emergency food during a famine. When Roman forces battled Jews, Queen Helene sent soldiers to help their Jewish brethren.

The Jewish kingdom of Adiabene lasted until 115 CE, when Roman forces crushed its leaders, but Kurdish Jews continue to regard its descendants as part of their Jewish community.

Holy Woman

One of the greatest Jewish scholars from Kurdish lands was a woman named Asnat Barazani, who led a respected yeshiva in the town of Mosul, in present day Iraq, in the 1600s. Asnat’s father Rabbi Shmuel ben Netanel Ha-Levi of Kurdistan built the school in Mosul to train a new generation of Jewish scholars – including his daughter. Perhaps because he had no sons, Rabbi Shmuel lavished care and attention on his daughter’s studies.

In a letter, Asnat described the intense education of her childhood: “I never left the entrance to my house or went outside, I was like a princess of Israel… I grew up on the laps of scholars, anchored to my father of blessed memory.”

Asnat married a fellow scholar, Rabbi Jacob Mizrahi, and had an unusual clause in her marriage contract: Asnat was never to be expected to perform any housework so that she could devote herself entirely to learning Torah.

After her husband died, Aseat continued to run the family yeshiva, which by then was plagued by financial problems. Asnat wrote a famous prayer, Ga’agua L’Zion, or “Longing for Zion”, which allowed many Jews to put their deepest hopes and desires into words of prayer.

Jewish Refugees to Kurdish Lands

In the 12th Century CE, some Jews fled violent Crusaders in Syria and the Land of Israel, finding refuge among the Jewish communities of Kurdistan. In the mid-13th century CE, Iraqi Jews fled from major Jewish centers like Baghdad as Mongol captured those areas; many moved north and west into Kurdish areas, joining the vibrant Jewish communities there.

As Jews poured from the land of Israel into Kurdish areas, David Alroy, an infamous Kurdish Jewish figure, arose. In the 12th century in the city of Amadiya, he raised a Jewish army and prepared to march to Jerusalem and liberate the city from the Crusaders. Before his Jewish warriors could depart on this mission, David Alroy was killed.

Accounts vary. The Jewish explorer Benjamin of Tudela wrote that he was murdered by the local sultan after encouraging Jews to rise up against their rulers. Some accounts maintain that Alroy was killed in his sleep by his father-in-law. After his death, some Jews falsely revered Alroy as the Messiah, even though his grand plan to come to the aid of Jerusalem’s Jews had utterly failed.

The Prophet Nahum

Kurdish Jews particularly revere the Jewish prophet Nahum who wrote about the end of the Assyrian Empire and its capital city Nineveh. Each year during the holiday Shavuot, Jews travelled to Nahum’s tomb, in modern-day Iraq, staging elaborate holiday celebrations there.

Local Jews described a major renovation of the tomb in 1796, paid for by wealthy Jews from Iraq and India. The tomb was owned and operated by the local Jewish community, and was a sumptuous center of gathering. A visitor during World War I described its splendor: the floors were covered with beautiful Persian rugs, and hundreds of notes with Hebrew prayers on them covered the walls. The building also housed lodging rooms where visitors could stay and pray.

After Kurdish Jews fled their homes for Israel in the 1950s, the Tomb of Nahum was cared for by a local Chaldean Christian family. They were not able to keep it up and today the building is largely in ruins. The tomb is located in a Christian village about 30 miles north of the Iraqi city of Mosul, which was the site of many bloody battles recently between ISIS fighters and local Kurds. Kurdish Peshmerga forces protected Nahum’s tomb throughout the fighting, preventing ISIS forces from destroying it completely.

Longing for Israel

Jews from Kurdish lands were intensely Zionist; generations longed to return to the land of Israel from where their ancestors originally came. Jews in Kurdish areas had contact with travelers and rabbis from the land of Israel, and learned Torah and heard news from them. In the 16th century, Kurdish Jews began moving to the land of Israel, settling in the city of Safed. Thousands more moved to Israel during the 1920s and 1930s.

Coming Home to Israel

Despite its vibrancy, life was hard for Jewish in Kurdish lands. Tribal squirmishes posed danger to many groups, including Jews, and the area’s harsh landscape made it difficult to farm and thrive. After 1948 when the State of Israel was established, life became even more difficult for Kurdish Jews, most of whom lived in present-day Iraq. Iraqi’s government passed a series of harsh decrees against Iraqi Jews, seizing their assets and stripping many Jews of citizenship.

The fledgling nation of Israel came to the rescue of Iraqi Jews, including the approximately 25,000 then living in Kurdish areas. Between 1949 and 1952, a series of airlifts, called “Operation Ezra and Nehemia” in honor of ancient leaders who helped restore Jewish life in Israel, brought over 120,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel. Many Jews from Kurdish lands settled in Jerusalem, often helped to flee the country by friendly Kurdish neighbors. Virtually all other Jews from Kurdish areas followed their brethren to the Jewish state; it’s estimated that only a handful of Jews remain living in Kurdish lands today.

Writer Ariel Sabar’s father was born in Iraq’s Kurdish north. He wrote about him and his family in My Father’s Paradise: A Son’s Search for His Jewish Past in Kurdish Iraq. “The moment his foot touched the ground at Israel’s Lod Airport near Tel Aviv” in 1951, Sabar wrote, “my great-great grandfather Ephraim began to cry. He dropped to his knees, bent forward, and kissed the tarmac.”

As Kurdish Jews stepped off the plane, they were amazed to find themselves in the land of Israel at long last. Sabar writes:

“The Kurds stepping off the Near East Transport planes in their hand-spun jimidani head coverings looked as dazed and disoriented as if a time-travel machine had just deposited them in a distant future. Parents descended the steps to the brightly lit tarmac with wary gazes and armfuls of children. Tired bodies clanked, with teapots slung to belt loops and demon-banishing amulets bunched at necks and wrists. Few had ever before seen an airplane, let alone traveled one.”

Sukkot and Saharane

For generations, Jews in Kurdish lands celebrated their own unique holiday, called Saharane, during Passover. It mirrored the non-Jewish Kurdish holiday Newroz, and featured singing competitions and outdoor picnics.

When Jews from Kurdish lands moved to Israel, some worried that Saharane was getting confused with another Passover-time festival, Mimouna. (Mimouna originated with Moroccan Jews and became popular in Israel. It’s celebrated the day after Passover concludes and is marked by visiting friends and neighbors for friendly meals and open houses.) In the 1970s, Kurdish Jews began celebrating Saharane during the Autumn Jewish festival of Sukkot instead.

Today, one of the largest Saharane festivals is held each year in Jerusalem, drawing over 10,000 participants for Kurdish Jewish food, music, and story-telling. In recent years, non-Jewish Kurds have even travelled to Jerusalem’s vibrant Saharane festival from Iraq, Europe, and elsewhere. In 2013, one Syrian Kurd now living in the Netherlands visited Jerusalem’s Saharane festival and explained to an Israeli journalist that even though she’s not Jewish, hearing the Kurdish music and watching people wearing traditional Kurdish dress made her feel at home: “We feel we are a part of Israel.” she explained about her fellow Kurds at the festival, who all received a warm welcome when visiting the Jewish state.

Life in Israel

Many Kurdish Jews entered the stonework and construction industries in Israel in the 1950s. Some Israeli towns such as Mevasseret Tzion and neighborhoods in Jerusalem housed vibrant Kurdish communities. Today, over 150,000 Israelis trace their heritage to Kurdish lands. The beautiful songs, foods, traditions and prayers of Jews from Kurdish lands continue to flourish in Israel today.

Photo at top: Refugee Jews from Iranian Kurdistan, 1950 © The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life

Source:

The modern-day region of Kurdistan.

An immigrant from Kurdistan arrives in Israel with her son, 1951.

(Photo: Israel Government Press Office)

Nahum's Tomb in Southern Kurdistan

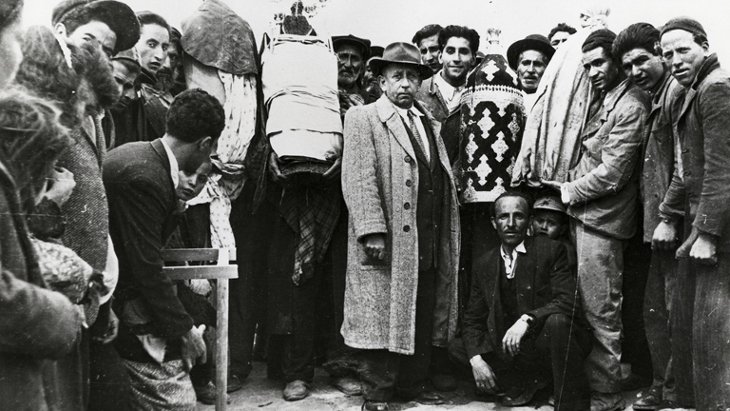

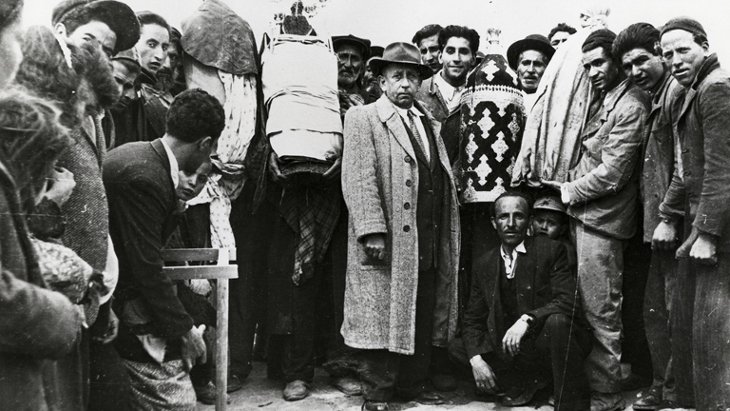

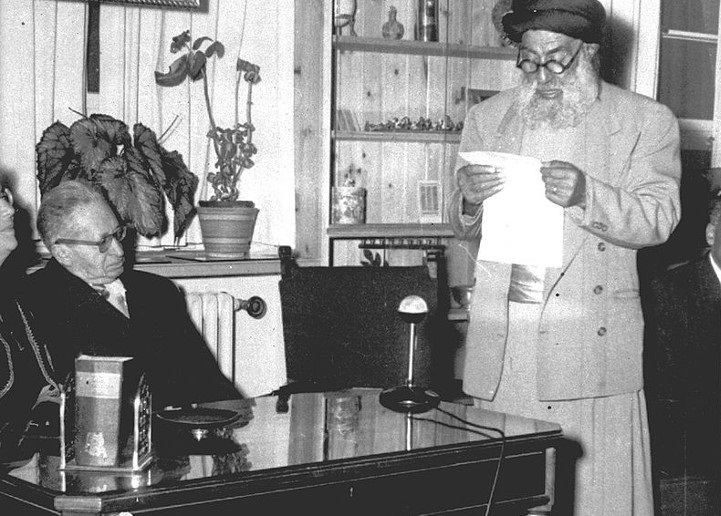

Rabbi Moshe Gabbai, head of the Jews of Zacho Iraq who immigrated to Israel in 1951.

He is petitioning then president of Israel Yitzchak ben Zvi to help his community.

Refugee Kurdish Jews in Tehran, Iran, in 1950. Via the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, UC Berkeley.

Celebrating at a SEYRANÊ festival

Xurakên kurdên cihû pir navdar in - Yahudi kürdlerin yemekleri çok meşhurdur

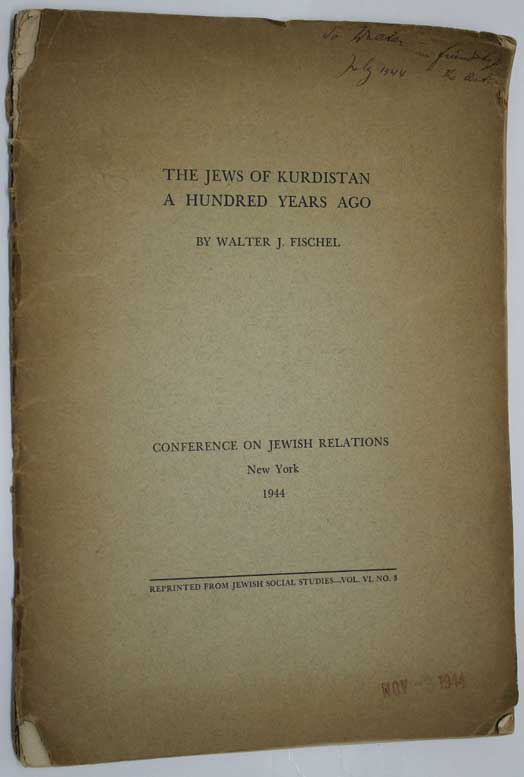

The Jews of Kurdistan A Hundred Years Ago

By Walter J. Fischel 1944

Media ..

Medians are one of the anccestors of the Kurds

Why do the Kurds have such a large population? Because the Kurds are the first, largest, homogeneous, settled tribe of the Middle East, which was formed by the union of dozens of great tribes.

(Kürdler neden bu kadar çok büyük bir nüfusa sahiptir? Çünkü kürdler onlarca büyük boyların birliğinden meydana gelmiş Ortadoğu'nun en ilk, en büyük homojen, yerleşik kavmidir).

Amida - Diyarbekir - دياربكر

Yahudileri

1848 yılında Diyarbekir’i ziyaret eden seyyah Benyamin Haşeni, notlarında orada yaşayan 250 yahudi haneden bahseder. Daha eskiye gidince, Başvekalet Arşivi’nde 15. ve 16. yüzyıllara ait icmal ve mufassal ve tapu kadastro genel kayıtlarına göre 1518-1519 yıllarında Diyarbakır’da 28 hane ve üç bekar olarak görülmektedir...

Asenath Barzani was the daughter of the eminent Rabbi Shmuel B Netanel Ha-Levi of Kurdistan (born 1560– death ca 1635/1670?) and she was a renowned Kurdish Jewish woman who lived in Mosul and died in Amadiya. Her writings demonstrate her mastery of Hebrew, Torah, Talmud, Midrash, and Kabbalah.

|

By Shira Leibowitz Schmidt

Around the year 1630, Rav Pinchas Hariri of Baghdad wrote to Mosul, Kurdistan, asking that they send a rabbinical authority to Baghdad. The letter was addressed to the director of the Mosul yeshivah. She replied that she would soon send one of her students.

She? Yes.

The administrator of the yeshivah in Mosul, a city 250 miles north of Baghdad was a woman—Asnat Barazani.

Barazani lived approximately from 1590 to 1670. Ami recently set out to ascertain the facts about this enigmatic figure.

After almost a century of academic controversy, the dust has settled. We have several extant manuscripts by Barazani, about her, and written to her. We know the basic outline of her life, and recent discoveries have filled in some of the lacunae.

Her grandfather, Rav Netanel Barazani, was a rabbi and Kabbalist in Mosul. Years later, his son, Adoni Shmuel Barazani, troubled by the relatively low level of Torah learning in Mosul, a city nestled along the Tigris River (Chidekel) in today’s Iraq, undertook to establish an educational system and yeshivah. His daughter, Asnat, was an only child. She was evidently a gifted student, and since he had no sons, he gave her the benefit of the finest education. She married his top student, Yaakov Mizrahi, but stipulated that she be relieved of household duties so that she would be free to study and teach.

She describes this in her own words in the first document to be brought to the attention of scholars by the early 20th-century German-Jewish anthropologist Erich Bauer, and by historian Jacob Mann:

“And [my father] made my husband promise that he would not make me perform work, and [my husband] did as [my father] commanded him. From the beginning, the rabbi [my husband, Yaakov Mizrahi] was busy with his studies and had no time to teach the pupils, so I taught them in his stead. I was a helpmate for him… [I undertook to garner support for] the sake of my father…and the rabbi…so that their Torah and names should not be brought to naught in these communities [of Kurdistan].”

The original Hebrew in the document was so full of Biblical, Talmudic and Midrashic language that the early researchers could not believe a woman had written it. However, as evidence accumulated, it became clear that the documents had indeed been penned by Asnat Barazani, the daughter of Rav Shmuel and the wife of Rav Yaakov Mizrahi.

Kurdistan

We have evidence that a Jewish quarter existed in Mosul in the seventh century, although local inhabitants claim that that their community goes back even further, to the first exile after the destruction of the Beis Hamikdash.

We do know that during the Crusades, many Jews from Eretz Yisrael took refuge in Mosul, which was safer than other locations and under Muslim rule and protection. We have records from Jewish travelers like Benjamin of Tudela, who visited Mosul around 1170, confirming that there were 7,000 Jews there at the time. Over the next few centuries the population waxed and waned, but in the 1947 census (when Mosul was under British rule), there was about the same number of Jews in the city.

The entire Jewish population, almost all traditionally observant, made aliyah when the State of Israel was created in 1948, and by 1955 almost no Jews remained.

In Her Own Words

Although some contemporary commentators have tried to portray Asnat as a proto-feminist, her own self-descriptions belie this image. In the handwritten manuscript first transcribed by Jacob Mann in his Jews in Mosul and Kurdistan, she writes the following:

“I never left the entrance to my house or went outside; I was like a princess of Israel, ‘kol kevudah bas melech penimah’… I grew up on the laps of scholars, anchored to my father, of blessed memory. I was never taught any work but sacred study to uphold, as it is said: “And you shall recite it day and night” [Joshua 1:8].”

She repeatedly refers to the expression “bas melech penimah” in her writings, and to the impropriety of going out to collect donations for the yeshivah. When her husband was niftar, both the administration of the school and the teaching fell to her. She rose to the occasion. She lived a penurious life, using all funds for the yeshivah. Evidently, she did much fundraising by mail. In an emotional appeal written in lyrical Hebrew, she shows her expertise in Jewish sources and her gift for poetry.

“I will cry out for Torah and sigh… There is no limit to my desire… The spark of light ignites the cloudy haze. … I call to you, my friends, I beseech you… I count on your generous spirit.” She concludes, “Raise the rays of light…that Torah should not be extinguished.”

The debts of the yeshivah were often so heavy that her own possessions were confiscated. “Nevertheless, I still continued to teach Torah, speaking on the subjects of family purity, tefillah, Shabbat and similar topics.”

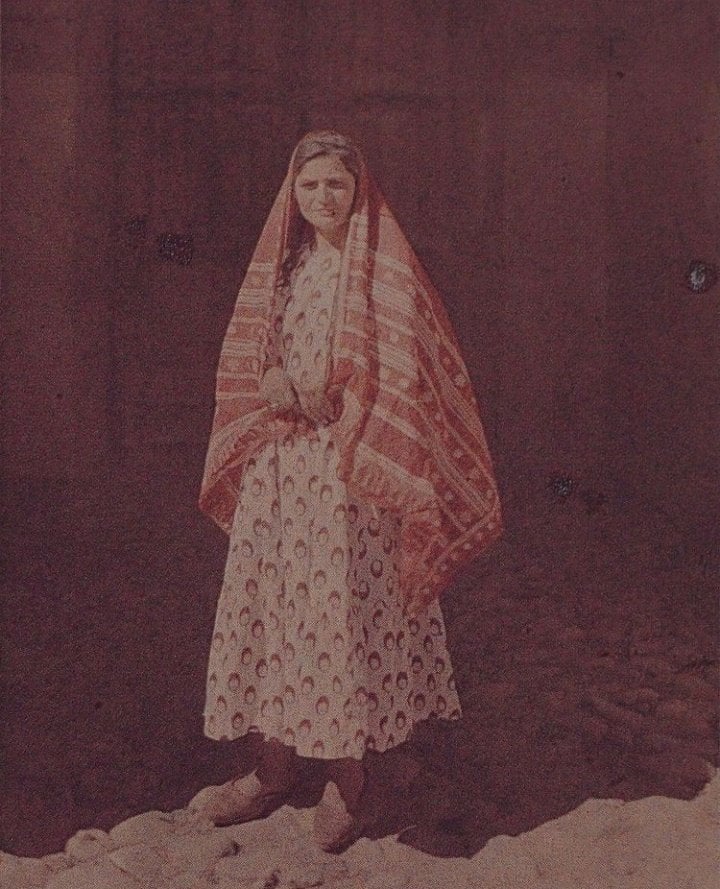

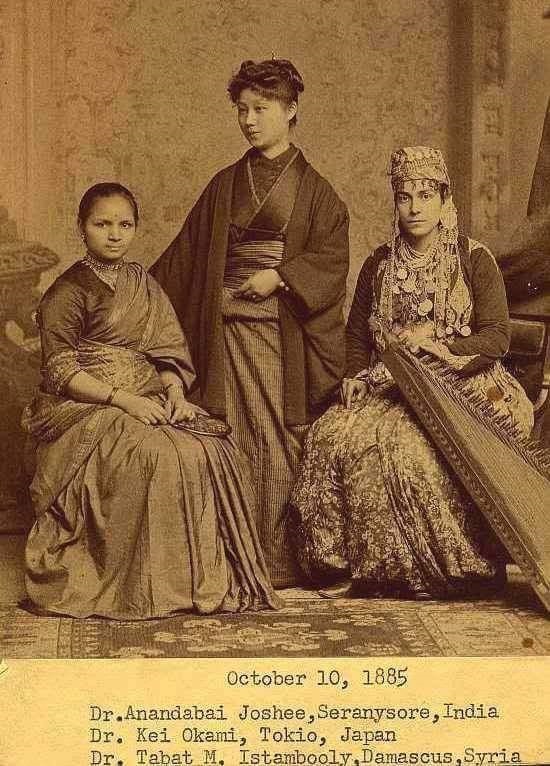

1885 - Dr.Tabat İslambooly Yahudi Kürd bir ailenin kızı 1941

__________________

Turks changed the name of the Greek metropole Constantinople to ISLAMBOOL (today Istanbul) which means full of Muslims in the city.

Turks forced both Constantinople's and Anatolia's Christian and Jewish families to wear this ugly and unjust name..

PICTURE (1885): The daughter of a Kurdish Jew family Islambools (1941)

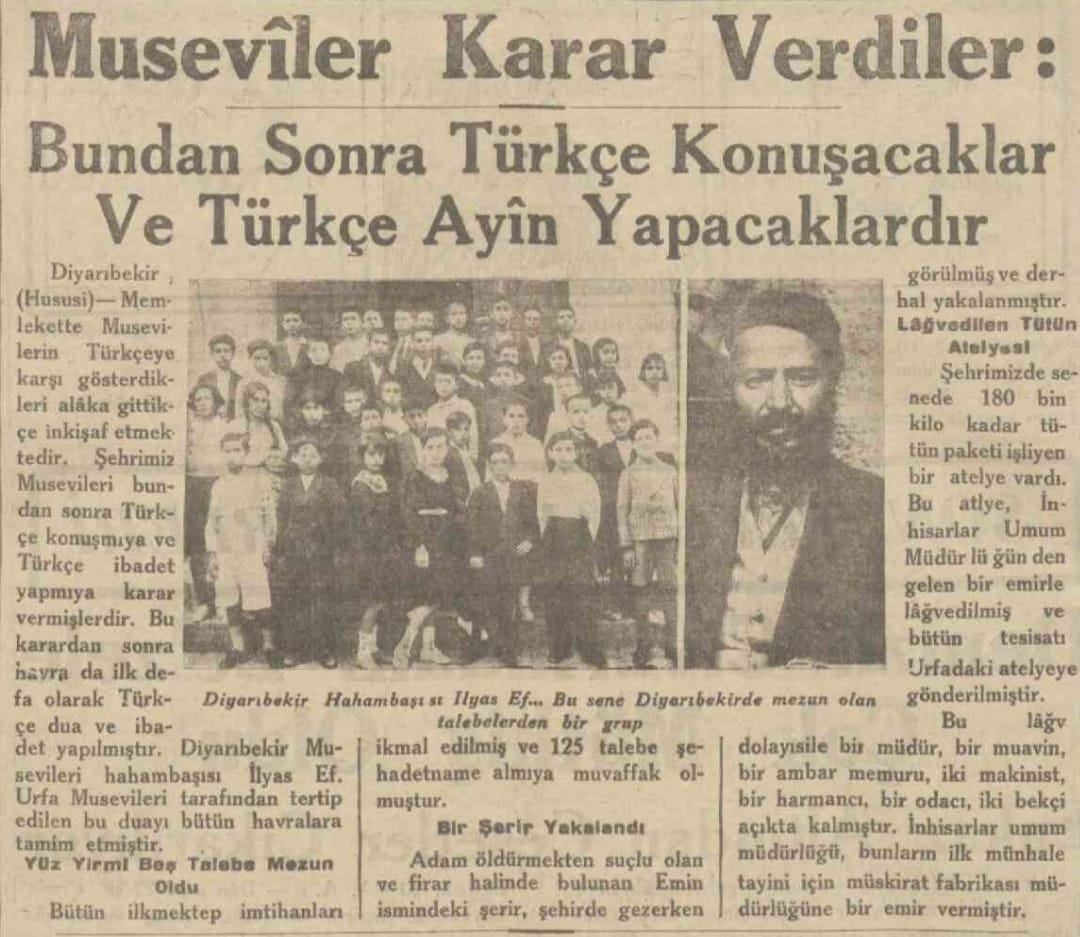

Turkish racist blasphemy of the 1940s: 'Jews decided, they will now speak Turkish'

They wanted to Turkify not only Muslim Kurds, but also Christian and Jewish Kurds.

Sadece müslüman kürdleri değil, hıristiyan ve yahudi kürdleri de türkleştirmek istediler

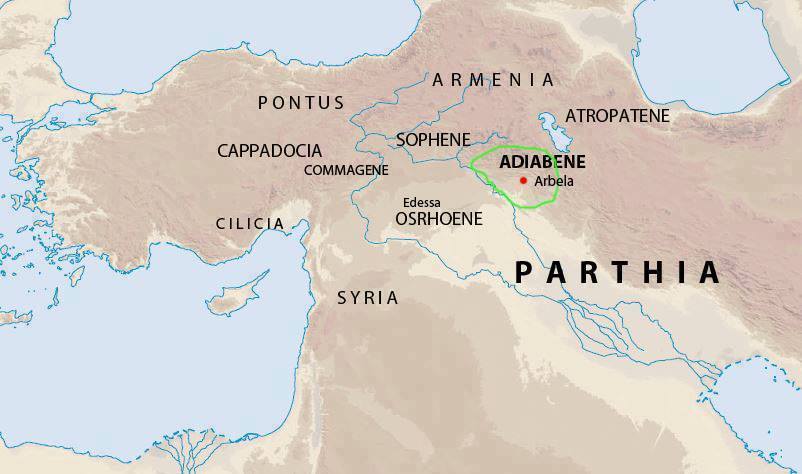

TARİHTE BİR YAHUDİ KÜRD DEVLETİ – ADİABENE KRALLIĞI

OBS: PARTIA is not PARS or PERSIA but it is a completely different group of people and is the ancestors of the Kurds,

such as the word of Iran, which means Aryans and has a greater overall meaning and in fact has nothing to do only with Persia.

The name of Iran was adopted in 1925 by Reza Shah instead of the name of Persia which the country had since before.

Yahudi (Musevi) Kürt yoktur, hepsi Batılıların ve milliyetçi Kürtlerin uydurmalarıdır diyenlere Adiabene Krallığı’nı örnek vermek yanlış olmayacaktır, Krallığın merkezi bugünkü Erbil´di. Eski adları ile Gılgamış’ın kardeşinin hüküm sürdüğü Urbilium, bu krallık zamanındaki adı ile Arbela´ydı. Bu krallık Hadhabani (Adiabani) isimli Kürt aşireti tarafından kurulan Musevi orijinli bir devletti. Genel olarak Büyük Zap ve Küçük Zap nehirleri arasında kalan bölgeyi tanımlıyordu, sonraları öncelikle Hadjab denilen kuzeydeki komşu sınırlarla bitişik bölgeleri de kapsamıştır. Süreç içerisinde bu krallık, Asur topraklarının büyük bölümünü içine alacak, Erbil en önemli yerleşim merkezi, dahası başkent olacak, Adiabene tüm Asur ülkesi için adlandırılacaktır.

Kürt tarihi en heyecanlı romandan daha da sürükleyici. Adiabene Krallığı’nın M.Ö 1. yüzyılda Yahudiliği kabul etmiş Kürtler tarafından kurulduğu tarihi kayıtlara geçmiş vaziyette. Kuruluş döneminde Partlara bağlı ama politik nedenlerden dolayı Yahudiliği benimsemiş yerel hükümdarlıkla yönetildiğini biliyoruz (Proselytismus). Partların kendi içindeki taht kavgaları ve Part-Roma arasındaki iktidar kavgalarına karıştıkları da kayıtlara geçmiş. Romalılara karşı Filistinli Yahudileri hem ekonomik hem de askeri açıdan desteklemişlerdir. Yine Romalıların, İsrail kentleri Judea and Samaria’ya zaptı sırasında (68-67), oraya asker yollayanların sadece Kürt Adiabeneliler olduğunu tekrarlamak gerekir. Galilee şehrinin kuşatılması sırasında da buraya yardım için bu krallıktan birlikler yollanılmasını tarihçiler, Adiabene Krallığı’nın Yahudi orijinli olmasına bağlar ve bununla gerekçelendirirler.

Kral Izates (Yazatas – Melek) ile özellikle annesi Helena hakkında sayısız kaynağa bugün bile ulaşmak mümkündür. Yine Kral Monobazos ve eşi Kraliçe Helena‚dan Mişna‚da (Yahudilikte Medeni ve Ceza Hukuk’u olan Talmud’un ilk bölümü) sık sık bahsedilir. Bu adların ilk din değiştirenler olarak muhafaza edildiği görülür.

Roma İmparatorluğunun Beş İyi İmparatoru´ndan (Evlatlık İmparatorlar –Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius ve Marcus Aurelius) ikincisi olan Marcus Ulpius Nerva Traianus (18 Eylül 53 – 8 Ağustos 117), namı diğer Trajan116 yılında Mezopotamya’yı istila eder. Adiabene´nin ismi Assyria (Asurya) olarak değiştirilip Roma´ya bağlı bir eyalet haline getirilir. Kürtler başta olmak üzere diğer Mezopotamya halklarından koloniler Trajan´dan sonra imparatorluğun başına geçen Hadrian (Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus (24 Ocak 76 – 10 Temmuz 138) zamanında bölgeyi tekrar ele geçirirler. Ama bunda Hadrian´ın önceli imparator Trajan´ın Roma’nın doğusuna dair izlediği istila politikalarından vazgeçmesi önemli rol oynamıştır. Hadrian Partlarla barış imzalamış, Hadrian’ın Yahudiye’deki Yahudi karşıtı tavırları Bar Kokhba ve Rabbi Akiva önderliğinde büyük bir Yahudi ayaklanmasına yol açmıştır (132–135). Hadrian’ın ordusu sonunda isyanı bastırır ve Yahudilere karşı Babylon Talmud’una istinaden dinsel baskı devam eder. Hadrian´ın barışçıl politikası, imparatorluk sınırları boyunca kalıcı savunma yapıları, özellikle duvarlar yapılmasıyla güya desteklendi. Bunların en ünlü olanı İngiltere’deki büyük Hadrian Duvarı’dır.

Yeniden Adiabene´ye dönecek olursak 195 yılında Roma imparatoru Lucius Septimius Severus Augustus namı diğer, Septimius Severus Kürdistan’ı yağmalar, ta Part imparatorluğunun o zamanki başkenti Chtesipon- Ktesifon (Tizpon) a kadar yollarının üzerinde ne çıkmışsa talan ederler. Binbir gece masallarına ev sahipliği yapmış, Partlardan sonra Sasanilere´de de merkez rolünü devam ettirmiş 800 yıllık başkentin, Halife Ömer zamanında Müslüman Arap orduları tarafından ele geçirilip yağmalandığını, arşivlerinin, kütüphanelerinin ve saraylarının yakılıp yıkıldığını İslam kaynakları ve Ekşi Sözlük aktarır. Septimius Severus´a Adiabene´yi yeniden ele geçirmesinden dolayı Adiabenus unvanı verilir.

Kürdistan Romalılar ve Partlar arasında sıkıştırılmış yolgeçen hanı gibidir. Yine 216 yılında Severus´un zalim ve diktatör oğlu Caracalla (Marcus Aurelius Antoninus) un yağmasına uğrar. Adiabene´de bu istiladan payına düşeni alır. Arbela (Erbil) kronikçileri Adiabeneli yöneticilerin, Kerkük hükümdarlığı ve Sasani Ardasir I. ile Part hükümdarı Artabanos IV´e karşı birlik olduklarını aktarırlar. Partlar tarih olup Sasaniler iktidar olduklarında Adiabene´de Hristiyan Nasturi cemaatlerine sıkça rastlarız. Romalıların tarihe gömdüğü krallığın yerini piskoposların idaresi almış görünür. Krallar sonrası evreyi en iyi Süryani kaynaklarının aktarabileceği ortada.

Aşiret mensuplarının bir bölümünün sürgüne maruz kaldıkları için Hadhabanilere, merkezi Kürdistan´ın dışında Horasan şehrinde de rastlanılır.

Adiabene Kralları

Artaxares, MÖ 30

Izates I., MS 30

Monobazos I. Bazaios, MS 30-36

Helene,

Izates II., 36–59/60

Monobazos II., 59/60–?

Mebarsapes, 114 civarı

116/7’den itibaren Roma İmparatorluğu

Adiabene Piskoposları

Pkidha (104-114)

Semsoun (120-123)

Isaac (135-148)

Abraham (148-163)

Noh (163-179)

Habel (183-190)

Abedhmiha (190-225)

Hiran (225-258)

Saloupha (258-273)

Ahadabuhi (273-291)

Sri’a (291-317)

Iohannon (317-346)

Abraham (346-347)

Maran-zkha (347-376)

Soubhaliso (376-407)

Daniel (407-431)

Rhima (431-450)

Abbousta (450-499)

Joseph (499-511)

Huana (511-???)

Süleyman Deveci

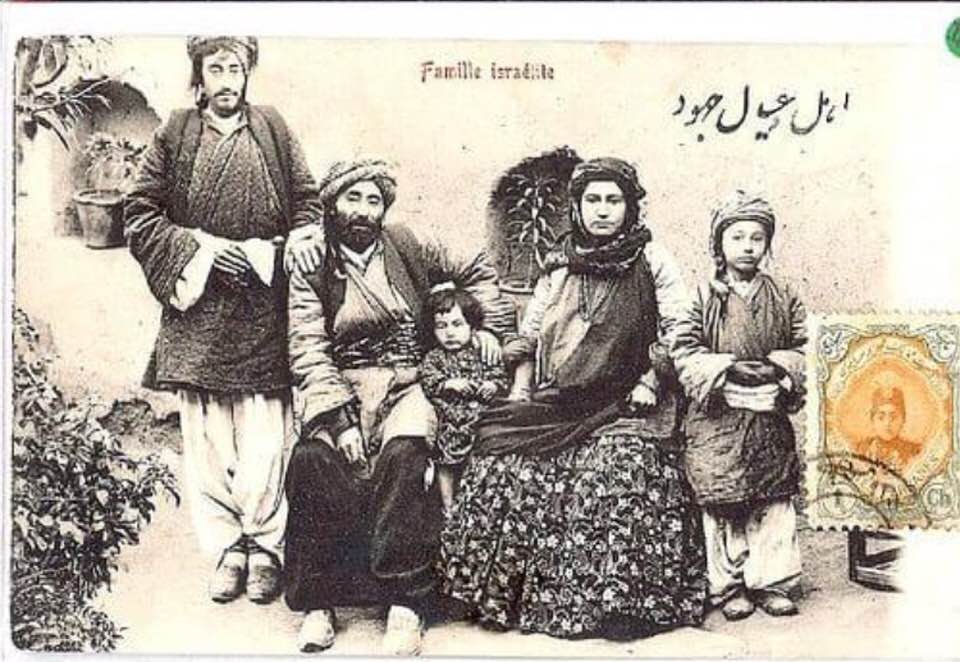

A Kurdish-Jewish Family in Eastern Kurdistan c1800

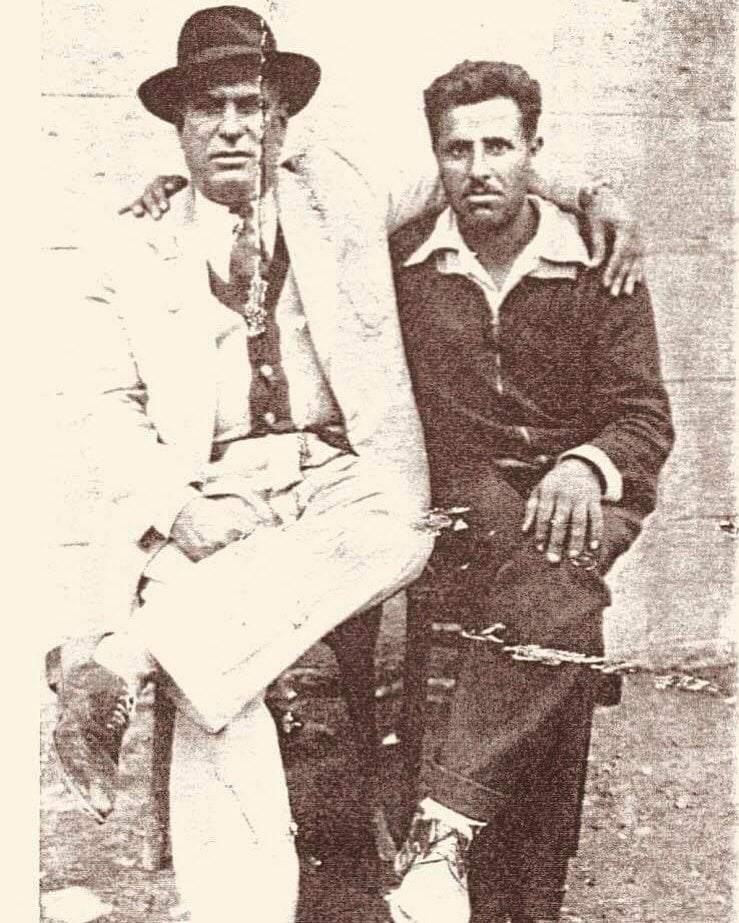

Du bira ji kurdên Cihû li Diyarbekrê. Ûsivê Mala Cîlo û birayê wî Saliho (Yehûda), 1951

The Kurdish-Jewish community's drawing of the traditional way of their life in Kurdistan on the walls of Jerusalem!

They lived in Kurdistan until Israel was founded. They want to belong to Kurdistan after they immigrated to Israel! This raises the question of whether they are diasporic or not!

Kürd-Yahudi toplumu Kürdistan'daki geleneksel yaşam biçimininin Kudüs surlarındaki çizimi!

İsrail kurulana kadar Kürdistan'da yaşıyorlardı. İsrail'e göç ettikten sonra da Kürdistan'a ait olmak istiyorlar! Bu, onların diasporik olup olmadığı sorusunu gündeme getiriyor!

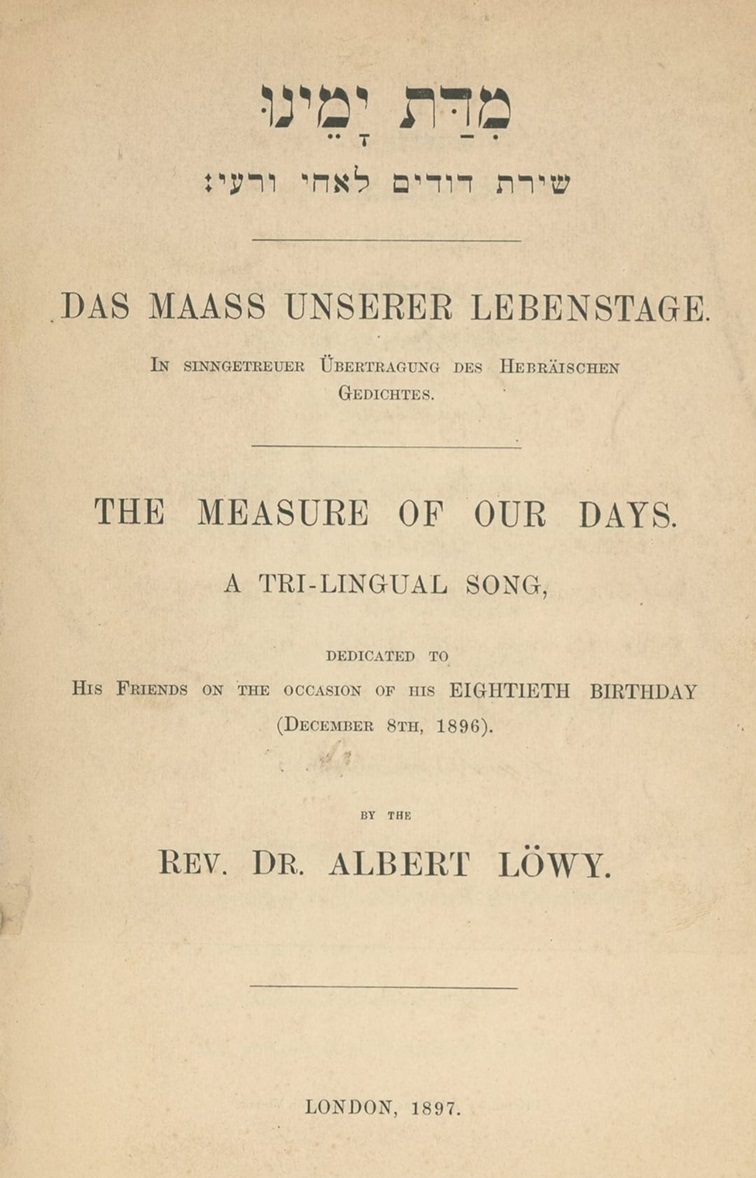

| Rahip Albert Löwy kiliselerin arkeoloji bölümünde çalışan rahiplerden biridir ve birçok çalısması kitaplaştırıldı Kral Meşha MÖ 900'de yaşamış, onun yazıtını çözen bilim insanlarından biridir.. Kürdçe ve kürderin yaşamlarının bir çok çivi yazısında geçtiği çalışmaları var.. 7 Mayıs 1878 Salı. ート |

S. BIRCH, LL.D., F.S.A., Başkan, |