Other Rank of Kut

1938

by

P. W. Long, M.M.

Flight Sergeant R.A.F.

with a Preface by Sir Arnold Wilson K.C.I.E., D.S.O., M.P.

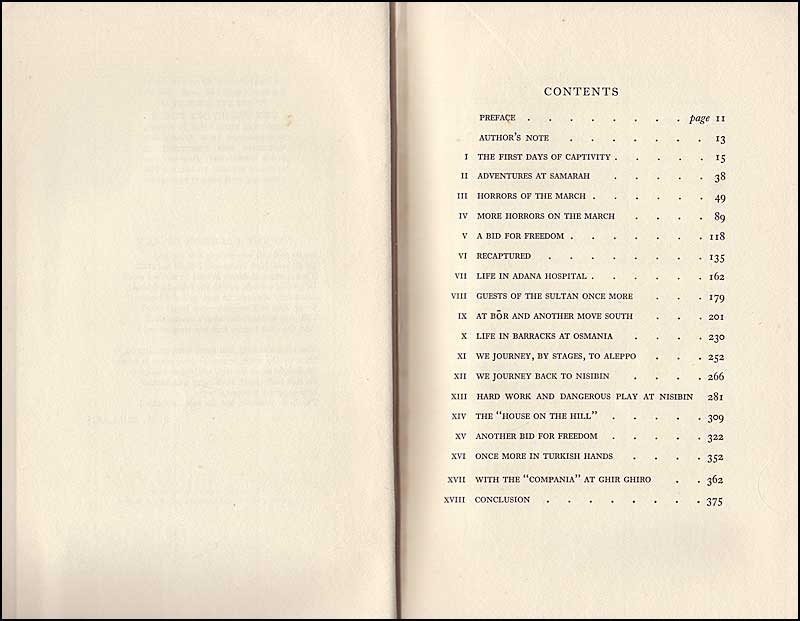

Bazar in Nsibin 1938

Kurds Of The Turkish Border Mountains 1938

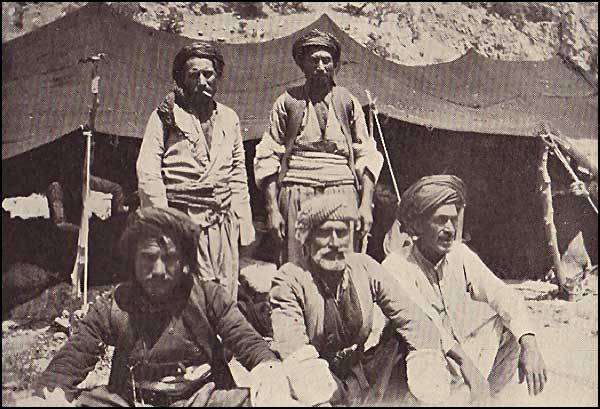

Kurds Outside A Goat's-Hair Tent

Kirkuk

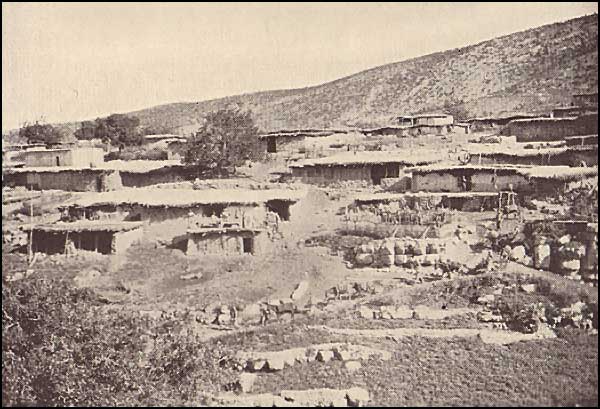

A Kurdish Village

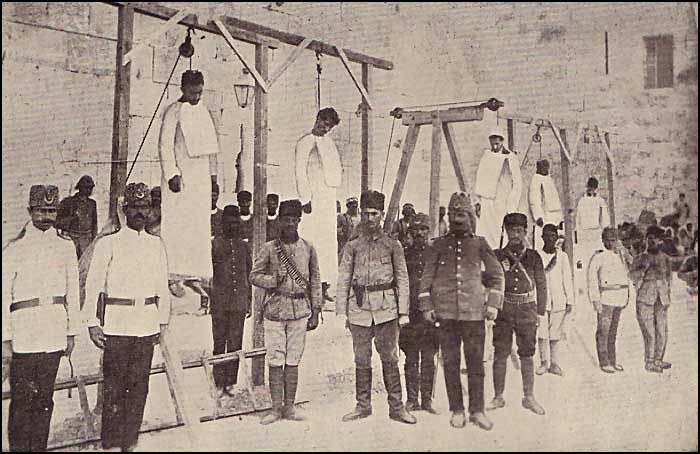

Mass Hanging

Long’s account starts on 30th April 1916, the day after the surrender of Kut, while he was lying on the “beaten earth floor of a mud hut that was graced by the name of No. 4 Field Ambulance.” There are many memoirs of men who served on the Western Front, but published accounts of “other ranks” who survived Kut and captivity are rare.

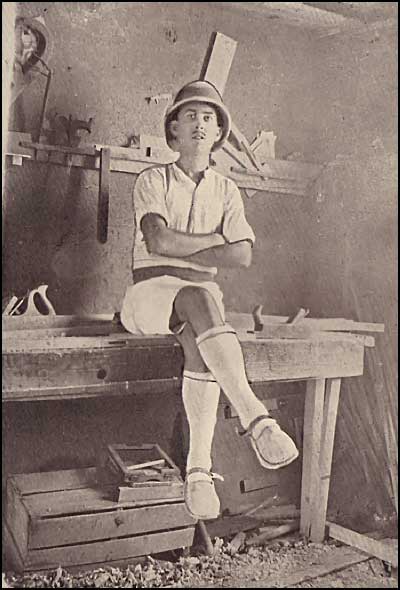

Author in a carpenter shop in Kurdistan

Contents

Preface Author's Note I. The First Days Of Captivity II. Adventures At Samarah III. Horrors of The March IV. More Horrors on The March V. A Bid For Freedom VI. Recaptured VII. Life in Adana Hospital VIII. Guests of The Sultan Once More IX. At Bor And Another Move South X. Life In Barracks At Osmania XI. We Journey, By Stages, To Aleppo XII. We Journey Back To Nisibin XIII. Hard Work And Dangerous Play At Nisibin XIV. The "House On The Hill" XV. Another Bid For Freedom XVI. Once More in Turkish Hands XVII. With The "Compania" At Ghir Ghiro XVIII. Conclusion Illustrations

P. W. Long

Bridge Of Boats, Baghdad

The Mosque At Kut-El-Amara

Author Laying A Wreath At The Newly Erected Permanent Memorial In The "Kut Plot," Baghdad Cemetery

Mosul Barracks

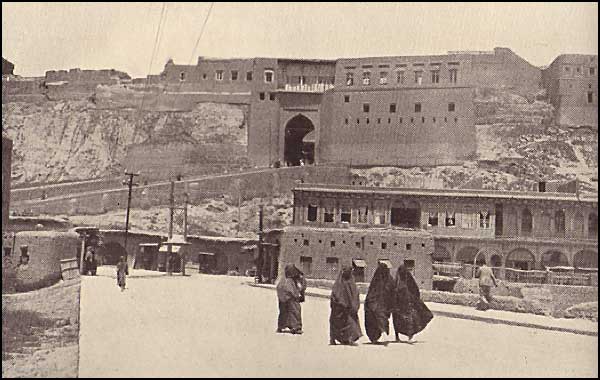

Mosul

Typical of The Kurds At Ghir Ghiro

The Old Guns At The Entrance To The Barracks, Mosul

The River Kharbur At Zahko

The Dreary Wastes Of Mesopotamia

The Bazaar, Nisibin

The "Kut Plot" In Baghdad Cemetery

Ctesiphon Arch

The Author at the Doorway of the House in Which He was Billeted during the Greater Part of The Siege of Kut

The Start Of A Caravan

Kirkuk

A Kurdish Village

Everyday Scenes on The Outskirts of Any Town or Large Village

A Large Riverside Arab Village, Showing The Huddled Manner of Grouping The Houses : Dens Of Vileness

Kurds Of The Turkish Border Mountains

Kurds Outside A Goat's-Hair Tent

Mass Hanging In Aleppo. Zaptiehs (Gendarmes) Wearing Brass Plates Round Their Necks, As Described on Page 259, can be seen at the back of the Scaffold between the First Two Hanging Figures

The Author In The Carpenter's Shop at Ghir Ghiro

The Kurdish Alps. Scenes Such as these are Prevalent in The Amanus, Anti-Amanus, and Taurus Ranges Through Which We Passed

Bedouin Crossing "The Blue"

PREFACE by Sir Arnold Wilson, M.P.

THIS book speaks for itself. It is from the pen of an eye-witness and is confirmed by half a score of independent narratives. The story has been told in a paper (Cd. 9208) presented to Parliament in November 1918 (before the Armistice): the Official History devotes six of its two thousand pages to the subject. Barber, Bishop, Keeling, Mousley, Sandes, Still, and Townshend are among the officers of the garrison of Kut al Amara who have published books dealing with the fate of British and Indian captives in Turkish hands. The public memory, however, is short. The belief, presumably of Crimean origin, that the Turks were clean fighters, who could be relied on to treat prisoners as humanely as circumstances allowed, has survived all evidence to the contrary. The parallel legend of Arab chivalry fostered by lilunt, encouraged by Doughty, and exploited for political and other less worthy motives during and for a few years after the war, seems scarcely less enduring.

Sergeant Long has done a service to the rising generation by placing on record, in the simplest language, the manner in which the Turks and their Arab associates treated their prisoners, as compared with the invariable consideration extended to the latter by German officers and, when opportunity offered, even at great risk, by Armenians, whom those who know neither Turk nor Arab sometimes so lightly speak of with dislike and even with contempt.

It is far from my desire to rake among the dying embers of contemporary history for sparks wherewith to kindle flames of hatred. Yet neither Sergeant Long nor I would have our fellow men ignorant of the profound difference between the attitude of this country to-day towards the suffering of helpless human beings and that of those Eastern peoples with whom we were at war. They were neither better nor worse than other nations with similar traditions and a like environment. Such happenings are a concomitant not only of war but of civil anarchy which may, as I know by experience, entail consequences worse than war to numbers of helpless individuals.

The treatment of prisoners, whether in war or in peace, has in all ages been inhuman, and in many countries still disgraces humanity. Scenes scarcely less terrible were, and perhaps are now, being enacted in other theatres of war.

Sergeant Long and his comrades were "the honoured guests of the Turkish nation." Their fate was long hidden from public knowledge, for the General Stall" in Mesopotamia discredited and, when possible, suppressed almost every report of cruelty and brutality till the bitter truth could no longer be hidden, whilst the Government spokesman in the House of Lords on May 16, 1916, was officially inspired to pay the Turks a tribute in respect of their treatment of prisoners "in comparison with other of our enemies."

The representatives of the United States of America in Turkey, notably the U.S. Consuls at Baghdad, Mersina, and Tarsus, did all that was possible, but it was little. Of 2,592 British rank and file taken prisoner at Kut, 70 per cent died in captivity. It is true that the machinery of civilization broke down everywhere: in Turkey it never began to work. If, God forbid, such things should happen to the world again, will the best-laid schemes fare any better ? To the historian the perspective of time is as vital as that of distance to the artist, and in human affairs progress must be measured in generations, not in calendar years.

But this story has a brighter side: it is a modest record of endurance and heroism of men of our race which lends point to the proud motto obscurely carved upon the cross bench of the House of Commons in front of the Sergeant-at-Arms:

"Numine et patriae asto."

"I stand by God and my country."

It lends point to the last stanza of a sonnet, To the Garrison of Kut, published in The Busrah Times by Mr. (now Sir) R. W. Bullard, of H.M. Consular Service, which appears on page 5 of this excellent book—the first work upon this subject to be written by one of the rank and file on whom fell the brunt. The author's repeated escapes, and the courage shown by him and his fellows, prove, if proof be wanted, the strength of character and capacity for leadership latent in men of our race even under the fiercest torments and bitterest physical miseries. Let those who proclaim the decadence of the rising generation—a favourite theme in 1913—read this book and ask themselves whether they, in like case, could do and dare as much as Sergeant Long.

ARNOLD WILSON

***

Author’s Note

When I decided to write this book I had one outstanding motive, and that was to put on record something that had not hitherto appeared in print; a record of the treatment meted out to the "other ranks" of the Kut Garrison during their long and terrible trek into captivity, also something of the life that they led as prisoners in the hands of the Turks during the years that followed.

Several officers had written of their various experiences, and most of them had touched upon the subject of the treatment that we of the "other ranks" had been subjected to, but they could not tell the full story for the simple reason that they were not permitted to accompany us— possibly one reason why we suffered as we did. One book was published as I was writing this, a book that is a compilation of brief accounts told by certain officers and men, with the result that it is a patchwork affair and does not satisfy us of the "other ranks."

For many years we of the rank and file of the Kut Garrison have waited for an author to come along to write the story for us, one who would do justice to the theme and leave us at last satisfied that the story of the annihilation of the greater part of the Indian Expeditionary Force "D" had been fully told. No such author has appeared, so I have, at long last, yielded to the many urgings by both officers and men of that generation and this, to write my story.

Each and every surviving member of the "other ranks," who passed along that trail of death into Anatolia, could tell a similar story to mine of what happened during that long march up-country from Kut. Many could, I have no doubt, tell of incidents more horrible than those I have described, but I know that what I have told concerning the experiences of my own particular party is, in general, the story of them all.

To my mind nothing has been lost by the long delay in making public this story. In the years that have passed since the days of which I write I have been fortunate enough to have been able to revisit Mesopotamia, and have passed over many miles of the route we were made to take as captives. I have fraternized with both survivors and descendants of those peoples who were responsible for adding to the sum of our sufferings, so that I have written my story confident that I have done so in true perspective; not unduly biased against our erstwhile enemies.

To-day I have a great admiration for the present generation of Turks who, led by that great soldier and administrator, Kemal Ataturk, are successfully striving to rid their race of the opprobrious epithet "unspeakable," and who are endeavouring to lift themselves from that position beneath humanity which many years of maladministration and corruption, practised and countenanced by their forbears, had thrust them.

To the many who have asked, and to those who would ask, "What happened to you after the surrender of Kut?" and "How did the Turks treat you?" this book is an answer.

P. W. LONG

MALTA. June, 1938

***

Chapter One

THE FIRST DAYS OF CAPTIVITY

"I have come to say good-bye, Jerry; we surrendered yesterday and to-morrow we march out."

It was thus that I learned that all our sufferings during five long weary months of siege warfare had been in vain.

Hardly in vain, perhaps, if one took the trouble to sort out the strategical niceties, but so far as the "other ranks" were concerned it was so.

The gallant 6th Division, I.E.F. "D," had fought their way from the Persian Gulf to the very outposts of Baghdad. Hundreds of miles of enemy territory had been won without I single reverse action, and we considered ourselves to be an unbeatable army, as indeed we had proved ourselves to be. Now we had been starved into surrender, but we remained unbeaten.

On office scribbling blocks and calendars and in books of reference can be found this information: "April 29, 1916. The Fall of Kut-el-Amara." Someone will read it and inquire: "Kut-el-Amara, wasn't that in Palestine or somewhere?" Like as not he will receive answer, "No, that was something to do with Allenby's crowd in Mespot."

Even the generation of that period are only dimly aware of what went to make another page of military history. Yet on that day thirteen thousand officers and men of Britain's Imperial Army were taken into captivity, and from then on were treated like the captives of the Old Testament days.

I heard the fateful news as I lay on the beaten earth floor of a mud hut that was graced by the name of No. 4 Field Ambulance. After several weeks of suffering from acute stomach trouble I had at last collapsed on duty, and had been carried there just as the ill-fated river steamer Julnar was making an epic attempt to get food through to the beleaguered garrison.

My pal of many years' standing had brought me the news, and, as he knelt and looked at my seemingly hopeless condition, the tears ran down his sun-blackened cheeks. It was plain that he regarded me as a dying man and that he was saying good-bye for the last time. It was our last good-bye, poor old Joe Cresswell died an agonizing death in a labour camp in the Amanus mountains.

The floor of the ambulance hut was covered with men in the last stages of sickness, and only when the dead were removed—which was all too frequently—could we stretch and move with comfort.

After my pal had gone I lay and tried to picture what it would be like to be a prisoner of war, until I was roused by a voice saying, "Come on, Cocky, you're going to the 'General.' " A cheery medical orderly was addressing me and I gathered that I was to be moved to the General Hospital. This hospital was actually the town bazaar, a street of open-fronted shops that had been commandeered for the purpose. Beds occupied the whole length of the roadway, and the shops were one- or two-bed wards.

I was placed on a stretcher and given in charge of two Indian orderlies and we set off on our way.

We had not proceeded far when our way was blocked by a yelling crowd of Arab townsfolk. My stretcher was lowered to the dusty road and the orderlies craned their necks to see what the excitement was all about.

Wearily, I turned my head to peer between the legs of the Arabs, who were crowding right up to my stretcher, and I saw the cause of the excitement.

A ragged company of Turkish soldiers was parading the town led by a gaudily dressed officer mounted on a sorry-looking Arab pony. The company was headed by two men who shrilled out a discordant wail on reed pipes. The soldiers were a most miserable-looking lot, sun-blackened and gaunt and altogether unlike a conquering army.

I closed my eyes and waited patiently for the Indians to pick me up and resume the journey to the "General."

I remember little of the rest of the journey until I heard a voice say, "Shove him in here."

The Indians carried me into a one-bed booth and lifted me on to a bed that had only a blanket covering the springs.

"Kutch nay mattrish, sahib ?"* queried one of the Indians.

"Kutch nay,"* was the answer.

What did a mattress matter anyhow ? I was almost beyond feeling, and was content to lay and dream of home and food, mostly of food. I soon drifted off into unconsciousness.

How long I was left alone that day I do not know, but I was awakened by someone saying, "Do you know me, Jerry?"

I opened my eyes and saw a horribly distorted face close to mine. It was fully a minute before I recognized in this piece of human wreckage a man of my own battery, one who had been in hospital for months, and was bent double from the effect of a shrapnel bullet that had travelled the length of his body from shoulder to ankle.

I mentioned his name and he said, "Blimey! you look rotten; what's the matter with you?"

"I don't know and I don't care so very much," I replied.

"Hang oh, and I'll find out," he said, and was gone.

Sometime later he returned with his information. "You're for it, Jerry," he commenced. "Enteritis, that's what you've got, and that's a posh name for cholera," he concluded. We were a cheerful crowd in those days and called a spade a spade.

***

Chapter Six

RECAPTURED

. . . The Armenian told us that only once or twice a week were they permitted to receive food, whilst the Turks and Arabs could get food as often as it was brought to them. All the scraps and water-melon rinds were thrown into the hole in the floor, which explained to us the reason for the horrible smell.

All that day we sat hoping against hope that we should get something to eat, but night came and again we went without. Our Armenian friend became very ill during the night, and I judged that it would not be long before he would be beyond the brutality of the Turks.

We were very faint from the lack of food when we went outside the next morning, and I begged the sentry to send an officer to us or to report our condition to his Chaoush. He pushed me away and said that he could do nothing.

We returned to our place at the window and stood watching the people passing in and out of the main gate, which was close to our prison. During the afternoon we saw an officer of the Gendarmerie approaching, accompanied by a man in European dress whom I thought might possibly be an American—the United States not then having declared war. As soon as they were within earshot I commenced to yell out in English at the top of my voice, continuing until I had attracted their attention, despite the threats of the sentry.

The Westerner said something to the officer, who shrugged his shoulders and appeared to be telling him to take no notice of us. Fearing that they would pass out of sight without coming to us I yelled out, "For God's sake get us out of here, we are Englishmen."

When he heard that the Westerner came over to us, followed by the officer.

"What are you in there for?" he asked us. We told him that we were escapees, prisoners of war from Kut-el-Amara. When he said "Mein Gott!" my heart sank, for then I knew that he was a German and not, as I had thought, an American.

Rapidly I told him of the state of the prison we were in, of the sick and dying men, of the daily deaths and our entire lack of food.

"If you cannot help us, then ask that police-officer to have us taken out and shot," I begged him. After all, such a death was preferable to one by neglect and starvation.

The German held a brief conversation with the officer, who finally ordered the sentry to unlock the door and let us out. We lost no time in getting out, and when the German saw the state we were in and caught a whiff of the fetid atmosphere of our prison, he looked shocked. He kept repeating, "Poor dears, poor dears," as I enlarged on the few details I had already given him, and he promised to do what he could for us.

We were taken to a small room near by in which a Chaoush and two Onbashis of the police were apparently in detention. The room was quite clean and had a raised platform inside on which to sleep or sit. The Onbashis were quite friendly and gave us some bread to eat as soon as we got inside, as they had heard all about us from the sentry of the prison. They were Arabs, but had served long terms of service in the police force of Adana. The Chaoush was an elderly chap who took no notice of us, but spent his time on his knees, praying and occasionally letting out a deep sigh and a very earnest "Alla-a-a-h!" Raoul Onbashi, the livelier of the two Onbashis, said that the disgrace of his punishment weighed heavily on the Chaoush, that was why he was continually in prayer.

Just before sunset we received a bundle of chupattis and a bowl of thick mutton stew, and, to our great surprise, a lira note. The soldier who brought those good things said that the food came from the Dowlat (Government) and the money from the Alliman (German).

We were too hungry to care who had sent which and in a twinkling were feeding like famished dogs, and about as daintily! Later on we discussed the kindness of the Germans whom we had met since we had become prisoners of war, and agreed that it was a great pity that they were now our enemies.

We asked Raoul Onbashi how we could purchase fruit and cigarettes with the paper money that we now had. He told us that if we wanted to change it into cash we should only get sixty out of the hundred piastres that it represented, but if we spent a quarter of it and got the change in paper then we should get full value for the quarter. So we decided to spend a quarter and Raoul called a sentry and told him what we wanted.

Our new prison boasted a hurricane lamp, and as we sat and chatted in the light of it we felt much better, and began to forget the nightmare existence of the past two days, especially when the sentry had brought the things we had ordered and we could puff at a cigarette.

We received a great kerchief of grapes and figs, bread-rings, and packets of tobacco and cigarette papers for our twenty-five piastres, and there appeared to be an amazing amount for the money. I asked Raoul how I could reward the sentry and was told not to worry about that as the stuff I had received had only cost twenty piastres, or less, and the sentry had taken the balance of the quarter lira for himself!

We sat and rolled cigarettes and offered some to our fellow prisoners. It was then that I discovered that we had forgotten all about matches. Raoul produced what he called a chekmuk, a flint and wool-cord lighter. It was the first we had seen of this novelty—a war-time product—and we little dreamed that even in England those economical lighters were in use and were to be the forerunners of the now universal petrol-lighter.

For several hours we smoked and chatted and I learned many things from Raoul that proved useful to me during the frequent sojourns I subsequently made in various Turkish prisons. I was surprised to learn that Turkish N.C.O.'s did not necessarily lose their rank when they were put into prison, as apparently good N.C.O.'s were hard to come by, and there was no other form of punishment for them.

The old Chaoush continued to call on Allah and did not join in the conversation. Neither did he join us when we feasted on the bread and fruit we had bought, though the two Onbashis made up for his absence!

The following morning we each received three loaves and were told that they represented the three days' rations we should have had since we had arrived at Adana. Someone was evidently looking into things on our behalf.

All would have been well had not the Sergeant begun to get pains in the stomach and bad headaches. Fortunately we were allowed out as often as we liked so that he was able to walk up and down outside when his pains became particularly bad. He became so bad that I asked the sentry to send for a doctor, though the Sergeant protested that he would be all right in a couple of days, and did not want any Turkish doctor messing him about! During the afternoon of the third day—after I had sent for a doctor—an official of some sort came to take particulars of our names and our fathers' names, etc. I pointed out the condition of the Sergeant, and said that he needed attention more than the Turks needed to know our fathers' names. Without any argument, and much to my surprise, the official sent for a sentry and told me to assist the Sergeant, and the sentry would take us to the doctor.

The doctor's surgery was not far away and in getting to it we had to pass through a rose garden. For a few moments we stopped and inhaled the fragrance of flowers that brought memories of England to us. It seemed to me a profanity that roses—of all flowers—should grow in such a corrupt land!

We passed on and, after a short delay, were admitted into the presence of the Hakim Effendi (Doctor). After a brief examination the doctor told me that the Sergeant must go into hospital, and, when I said that I had better go with him, informed me that there were many British soldiers in the hospital in Adana. That was news indeed, as we had no idea that any Britishers were within miles of us. I begged the doctor to send me along with the Sergeant, saying that I, too, was very sick! He examined me and smiled, and shook his head. It was no use, we had to part; I to return to prison and the Sergeant to go to hospital, I was very sorry to see him go alone, but I knew that he would never get better unless he had some sort of treatment, and he would have the company of other Englishmen also.

The following morning I was taken from the remand prison to the mappus khana (prison house), the main prison of Adana. I made the journey by arabah, the Turkish equivalent of the arabana of the Arabs, a flat-bottomed, springless, four-wheeled cart, held together by odd bits of wire and string and of uncertain age. I was rattled and jolted along at a breakneck speed through the streets of the town, and was very pleased when we arrived at the prison on the outskirts.

I was at once surrounded by soldier-warders and pretty thoroughly searched. The Chaoush in charge took from me the broken crucifix that I had—for no apparent reason— carried all the way from Jezerieh-ibn-Oman.

The prison was a large mud-built thatched building similar in shape and design to the familiar "army huts" of war days. Down the centre of its length was a roof-high partition, which divided the sleeping quarters of the warders from that of the prisoners. A small wicket-gate gave access to the prison through the partition, and an armed guard was posted on either side. Through this gate I was led and introduced to the inmates by the Chaoush bellowing out "Ingleezi!"

I was immediately surrounded by a gaping crowd of civil prisoners of many races and many degrees of uncleanliness. I pushed my way into the centre of the long room and stood undecided what to do next. Suddenly a voice shouted in English, "Oh, there! are you English?" I turned and saw someone waving to me; I went up to him and said, "Yes, I am English."

"Cripes! but you certainly don't look like one!" said the speaker; and I certainly did not in comparison with him. He thereupon introduced me to two others who were his companions and I learned that they were Australians, would-be escapees from a working camp in the Taurus Mountains, called Belamadik. They proved to be rare good fellows, and it was fortunate for me that they had been long enough in prison to have learned all the schemes and wangles that go to make life easier in a Turkish prison.

Among other things they told me that they were daily expecting to be released and sent back to the working camp. That did not cheer me up at all, as their release meant loneliness for me. However, by the time they did go, some nine or ten days later, I was fairly conversant with all that went on in the place.

By some means or other they had got into touch with the American Consul at Mersina who had sent them money, clothes, bedding, and sundry other things. They promised that they would get the same for me; meanwhile they were good enough to share what they had with me.

I speedily realized that those three "Aussies" had established a tiny bit of the Empire in that foul prison. The other prisoners held them in great respect and all the warders were very friendly towards them and allowed them many privileges.

They sent for a barber and paid him to give me a shave and a close-crop haircut, after which they helped me to have a good wash down—using real soap!—and, when it was all over, I both felt and looked a different man.